in·ter·rupt (nt-rpt)

v.in·ter·rupt·ed, in·ter·rupt·ing, in·ter·rupts

1. To break the continuity or uniformity of: Rain interrupted our baseball game.

2. To hinder or stop the action or discourse of (someone) by breaking in on: The baby interrupted me while I was on the phone.

3. To break in on an action or discourse.

All three of these are important to us at work. While we are working, we are achieving (hopefully) a state of flow. Both in the psychological and the mechanical sense of the word, we are actively focusing, working, and completing the task at hand.An interruption is anything that breaks that flow-state. <The phone just rang. On call for 2m13s.>When we break that flow state, just like that side comment about my own interruption broke up the flow of this post, we have several states we transition through:

Initial shock (Oh my god, I’m being Interrupted!)

Adjustment (Context switch into new context)

Existence (Live in new context)

Closure (Close off new context)

Return (Return to previous context)

Depending on the detail needed by the interruption, these states can take take minutes, tens of minutes, or more. Luckily for me, my interruption was minor and rather fun, so leaving the blog post and coming back was relatively easy.

Interruptions and You

Since most interruptions are small, routine, and often important, we tend not to notice them. When interruptions are annoying, we do notice them. Then, when we are late in finishing something, we will blame our lateness on the annoying interruption and conveniently forget all the other ones.The fact is that interruptions are part of knowledge work. We seldom do it alone, which means we have colleagues. Colleagues require information. Information requires communication. Communication requires attention.We are also social animals. So, if I come into your office and say, “Hey, I need to talk to you about the Amalgamated Salamander contract,” you are likely going to say, “Okay,” and we’ll talk. Even if you say “No,” you are unlikely to simply say “No,” and ignore me from then on, because that’s rude. And if you are truly rude, you will not stop at “No,” you’ll tell me exactly why you don’t have time for me which is still an interruption.We cannot declare interruptions as waste, either. Knowledge work and personal work is fraught with rapid changes in context. Micropriorities that never existed on your project plan crop up every day. Like “Hey, Barb’s out sick, you still want to have that meeting?” Or “I just got this fax from the FDA and they are claiming that epoxy isn’t a food and we have to pull our Gluey-Chooies off the market.” Things like that.So, we need to understand what our interruptions really are, before we decide that we want to eliminate them.There are many systems out there to help you isolate yourself from interruptions, but completely closing yourself off from change – in an environment with high degrees of change – doesn’t make a lot of sense.

Understanding Interruptions

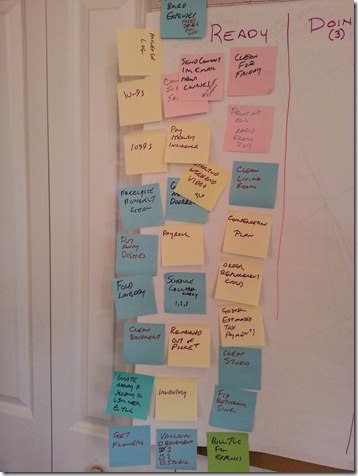

In order to know a thing, you must become a thing. So, you must first go out and interrupt as many people as you can.No … scratch that.In order to understand interruptions, a good place to start is to (surprise) visualize them. Here are some suggested ways in increasing levels of complexity.Write Them Down: That’s simple enough. Keep a pad of paper nearby and when you are interrupted by ANYTHING write it down. Even if you are interrupted by daydreaming about how awesome lunch is going to taste.Add Them to Your Kanban: Get a special shaped sticky notes, like maybe ones shaped like the human cochlea (or something) and add substantial interruptions to your board. This way you can track them and see them mixed with your other work.Record Severity: Create a table on a sheet of paper. 8 rows for the hours of the day, and 12 boxes for five minute increments. Then color in the boxes during which you were interrupted from your primary task.Now that you’ve recorded them. Ask some key questions:

Are these interruptions necessary?

Did I provide or receive value while involved in this interruption?

Does this interruption happen frequently?

Can I schedule this interruption, making it a planned event?

Did I have the time and mental capacity to help with this interruption?

Again, the goal is not to eradicate interruptions. The goal is to understand them and work with them. Some will be waste and you can remove them. Some will be part of your job and you must find elegant ways to work with them.

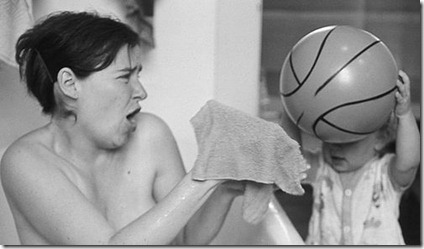

Limiting Work in Progress

After you understand the nature of your interruptions, you can build much more resilient strategies for limiting work-in-progress. We can limit unnecessary interruptions, understand when it is appropriate for us to sequester ourselves in a Pomodoro, and structure our work to allow us to stay as much within our WIP limits as possible.Photo: “Dorrie Interrupts Sissy Bathing” by Paul Schultz.